Learning Styles are a Myth

tl;dr:

learning styles are a myth - it’s a bad way of thinking about individualized learning

What we need instead is a better understanding of the learner, and in particular, what they already know so that we can match them with the appropriate level of difficulty for their capacity. That involves creating scaffolded learning experiences that start with narrated examples and moves towards independent practice.

Here’s the argument:

In order for learning styles to be true, an experiment needs to validate their existence. This is what the experiment would look like (adapted from Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence)

Learners:

state their desired learning style (Vistual, Auditory, Reading, Kinaesthetic)

are grouped according to their learning style

are taught in accordance with their learning style

are assessed using a learning style agnostic test

are then taught and assessed using their non-preferred learning style

The results from the first test (4) must outperform the results from the second test (5). Because of the lack of evidence for the claim that learning styles exist, the authors conclude “at present, there is no adequate evidence base to justify incorporating learning styles assessments into general educational practice.” Other authors have come to the same conclusion. So the methodology that would need to be followed in order to demonstrate the effectiveness of learning styles does not exist. Why, then, is the idea of learning styles so pervasive?

There is an intuitive appeal to the idea of learning styles. For example, someone recently was telling me that she prefers a book (reading) because sitting and listening to a lecture (auditory) does not work effectively for her. She sees that it works well for others, but not for her. Likewise, some people claim that they need to talk through (auditory) the information in order to make sense of the information. In both of these situations, there is a misunderstanding of what is happening during the learning process. In order to learn and retain information, that information needs to be made meaningful by being related back to previous experiences. For example, someone during a lecture might be talking about managing addisonian crises. Someone who is a novice learner will likely need to take their own time and work through the specific details of the case (look up reference material, learn the mechanism of action, etc.) whereas someone who is an advanced learner might quickly understand what the crisis is and is only looking for the information on how to manage the case. The novice learner will then have a hard time following the lecture whereas the advanced learner, having sufficient background information to relate the case to, will only need a few words in order to advance their own learning. In sum, it’s not the style of learning that determines acquisition and retention of information, but it is the match between the learner and the complexity of material that is a better determinant of the learner’s success.

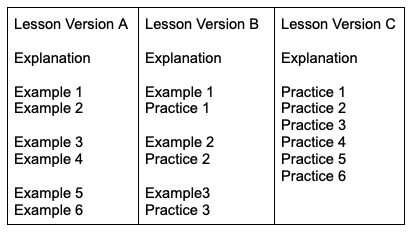

What is the alternative to learning styles? In principle, the idea of tailoring the information to the needs of the learner is a good one. What is not good is using learning styles as the framework for determining how material should be presented. An alternative, and one that is more in line with the literature on learning, seeks to categorize the material based on a spectrum from novice and simple to advanced and complex. For novice learners, using worked examples is best. A worked example is “a demonstration that illustrates a specific sequence of the steps to complete a task or solve a problem.” (Clark, 208) What starts with demonstration, ends with practicing. In each succeeding lesson, the learner takes on a more active role in the learning. Here’s how Clark visualizes this process:

The learning experience is scaffolded for the individual. This kind of scaffolding works really well for skill acquisition, such as problem solving, or manual skills such as surgery or mechanical repairs.

This kind of learning relies on inductive inferences: extrapolating from many instances to general principles and abilities. This is a more effective way of learning than deductive inferences: learning the general principle and trying to figure out the context for that principle. In the first, the guesswork is taken out of the situation because the learner is working through the individual situation to create the principle that should be applied in the future, and so understanding when it should be applied has already been practiced. Whereas with deductive learning, the individual learns principles but doesn’t know precisely where/when that information should be applied. This introduces a level of extraneous cognitive load that is unnecessary for the learner.

References:

Clark R. & Safari an O'Reilly Media Company. (2019). Evidence-based training methods (3rd ed.). Association for Talent Development. Retrieved November 3 2022 from https://learning.oreilly.com/library/view/-/9781949036589/?ar.

Coffield, F, Moseley, D, Hall, E & Ecclestone, K 2004, Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: a systematic and critical review, Learning & Skills Research Centre, London.

Kirschner, P. A., & van Merrienboer, J. J. G. (2013). Do learners really know best? Urban legends in education. Educational Psychologist, 48(3),169e183. http:// dx.doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2013.804395.

Kirschner, P.A. 2017. “Stop propagating the learning styles myth.” Computers and Education, 106, 166-171

Pashler, Harold & Mcdaniel, Mark & Rohrer, Doug & Bjork, Robert. (2008). Learning Styles: Concepts and Evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 9. 105-119. 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x.